Will the Movie Industry Contract in 2017?

Originally published in Cultural Weekly on January 4, 2017.

Movies are going gangbusters, and one studio—Disney—achieved a record-breaking $7 billion global box office last year. What could possibly go wrong?

According to my analysis of historical patterns, we’re due for a downturn. The film industry is often likened to a roller-coaster because we experience it as having surprising ups and down. The analogy is even more precise than we would like to think. Just as a roller-coaster rises and falls on a fixed and predictable track, so too the film business has an uncanny, regular pattern of peaks and valleys.

I first became aware of this pattern in 1988 as a junior executive at Walt Disney Studios when the Writers Guild went on strike. The strike lasted 155 days, during which time no new screenwriting took place, and even after the strike was over it took years before movies and TV shows achieved full levels of production. I imagined this was an unpredictable economic event. But when I talked with some of the old-timers, people who had been in the financial offices of Disney and other studios for decades, they told me it was to be expected: they didn’t know the writers would go on strike, but they had been certain the movie business would have a downturn in the late ‘80s. They had seen the pattern before.

How could that be? I started to do some research, going back to the beginnings of filmmaking in 1891, when Thomas Edison patented the kinetoscope, the precursor to the motion-picture projector. I discovered that innovations in technology and distribution have been driving the movie industry through rising and falling economic cycles, and that the cycles happen in a predictable, ten-year pattern.

I first wrote about this phenomenon in Screen International magazine in December, 2009. My editor dubbed my observations “The Leipzig Hypothesis.” At that time the movie business was in a downturn, and I predicted that the cycle would start to turn up in 2012. It did.

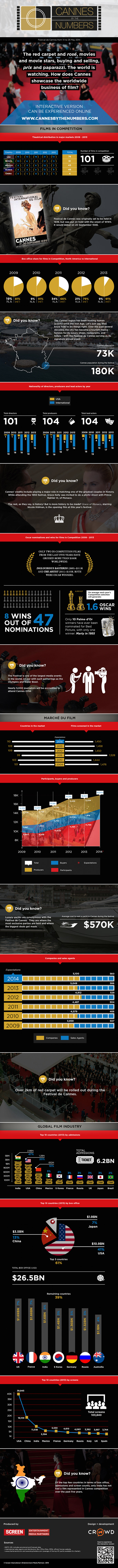

My hypothesis states: The film industry’s expansion and contractions — based on known milestones — for the last 120 years has followed a wave pattern which peaks with uncanny regularity in the middle years of each decade, then bottoms out in the decade’s last years, only to rise again from the ‘0’ year driven by new innovation. It looks like this:

I admit that the Leipzig Hypothesis is somewhat impressionistic. It relies, in part, on verbal data I got in conversations with finance people who had been in the movie business since the 1950s. It’s difficult to evaluate the entertainment industry’s profitability from the outside; studios play fast and loose with the numbers so it’s been hard to measure historical ups and downs. Box-office numbers, even when adjusted for inflation (which they usually aren’t) account for only a fraction of a film’s revenue, and today box office revenue matters less than it ever has before, because of the films being financed by streaming services Netflix and Amazon.

In addition, domestic numbers often seem to show patterns that alter radically when currency-fluctuating (and poorly counted) foreign sales are thrown into the mix. So the movie industry, unlike more numerically minded businesses, is never really sure whether its economic viability is rising or falling; it has always seemed more of a gut feeling, at least to people outside the highest levels of the industry.

However, based on my nearly three decades in the business, my knowledge of studio balance sheets, and my interactions with the financiers who keep this industry spinning, I’m ready to go out on a limb once again and predict that a contraction will happen starting in late 2017 or early 2018, and filmmaking will feel an economic downturn. If the hypothesis holds, it will make the movie business a bit more quantifiable for everyone. If the hypothesis fails – which it may, due to significant changes in business models – we can put it to rest as a historical artifact.

Here is how the hypothesis has functioned historically. (See infographic below.)

In the early years of each decade, as an innovation takes hold, the business tends to expand. There’s a sense of renewed optimism among industry executives and bigger movie budgets soon follow, along with higher salaries and richer deals for the talent. The expansion generally peaks around the sixth or seventh year of each decade, when higher spending has taken its profit-reducing toll.

Then, pessimism sets in, and industry leaders call for the business to be reined in. Budgets become smaller and negotiations become tougher amid prognostications about the ill health of the industry. In the final few years of each decade, which we are entering now, the business contracts, reaching its nadir at decade’s end, when, almost miraculously, the next innovation is born that will start the cycle anew.

Each innovation is an advance in technology or a new distribution market. For example, in 1900, the size of each reel of film doubled, allowing longer, more complicated takes. In 1910, black-and-white movies were enhanced with two-color tinting. Technicolor was chartered in 1921 and the first film in Technicolor’s Process 2 was released the following year. Synchronized sound technology started in 1927; silent movies ended in 1929. Then 1940 saw the advent of multi-channel sound; the screen image became much wider in the early 1950s with the innovation of CinemaScope; and special effects took a leap forward in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

New distribution markets have been the drivers for the past 40 years, beginning with the first multiplex cinemas in 1970, and the creation of HBO and cable television in 1972. Then, in 1976, VHS and Betamax videotape appeared, starting the trend towards in-home entertainment, which became widespread by 1980. The foreign markets exploded in 1990: films began making more money overseas than from the domestic market, and a new internationalism began to take hold in Studio-land. DVDs began to explode in 2000.

The most recent expansion was due to wide adoption of another new technology: streaming video services. Although Netflix began its streaming service in 2007, it really took off in 2012 when it went public and was able to grow exponentially. Since then, Netflix has grown from 27 million subscribers to more than 86 million today, and has a presence in more than 190 countries. Amazon Prime began streaming original content in 2013 and now has nearly 70 million subscribers.

I feel it is an open question if the hypothesis will continue to hold. For the first time, it is hard to quantify exactly what the movie business is. When Netflix and Amazon finance or acquire feature films to exploit their value on their streaming services – not at the box office – and further, not reveal how many people are watching (which they don’t) there is no way to tell if movies are economic success or failures. As Michael Smith and Rahul Telang posit in their book Streaming, Sharing, Stealing, the power-center of the movie business has moved from companies that create content (studios) to companies that own their audiences (Netflix, Amazon, YouTube, iTunes). This shift is fundamental, unstoppable; we may need a new model to predict expansions and contractions.

On the other hand, the cycle may hold. For one thing, the U.S. dollar is at record-level strength against other currencies, which means that international revenue will be lower than projected – this alone could incite a contraction. Also, the content acquisition budgets for Netflix ($6 billion) and Amazon ($3 billion) are unsustainable and both companies will probably begin to ratchet back their spending in the next couple of years.

My conclusion? Let’s find out together. I’ll meet you back here at the beginning of 2018 to take the pulse of our business again and see where we are on the roller coaster.

Film Industry Cycle Infographic